The widening economic gulf between Europe and the U.S. is inspiring a bold idea in Brussels: the creation of a pan-European capital markets union. Advocates claim a unified continental financial ecosystem could reinvigorate the European economy, but numerous barriers stand in its way.

The European Union’s (EU’s) “four freedoms” seek to guarantee the free movement of people, goods, services and capital across 27 member nations. It is these principles that allow shoppers in a Prague supermarket to pick up a bunch of Spanish grapes as easily as a New Yorker can grab a Florida orange at the corner deli. Yet, despite remarkable progress over the past 30 years in developing a single currency, seamless internal migration and tariff-free trade, when it comes to the movement of capital, the EU still falls short of its ambitions.

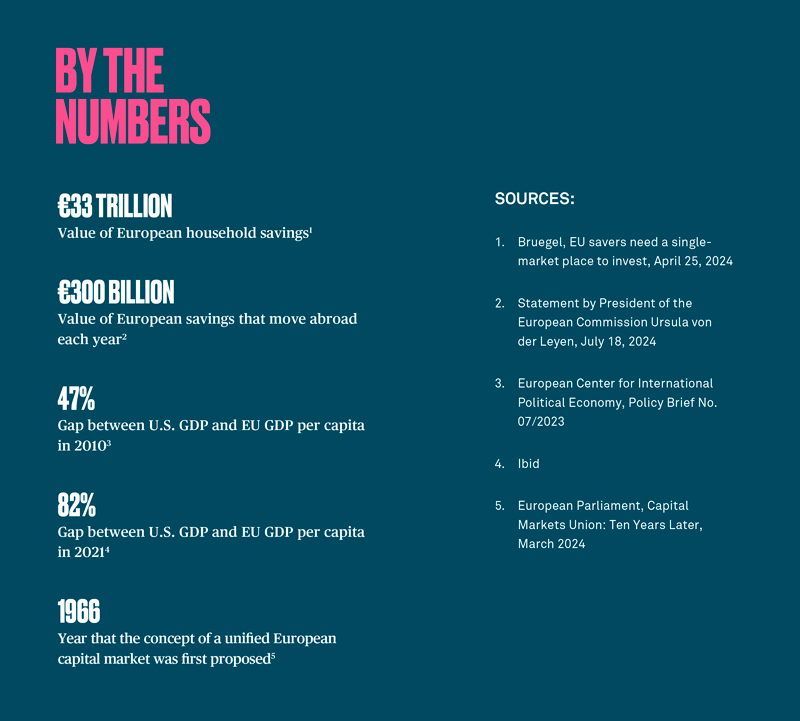

Efforts to ease intra-EU fund flows date back to the 1960s, but there seems to have been little in the way of progress in the intervening decades. That may at last be changing. The European Commission (EC), urged on by national leaders, is gearing up for a new attempt during the next European Parliament. Advocates argue that the effort could unleash Europe’s €33 trillion of household savings to jump-start economic growth across the continent.

The goal is a capital markets union (CMU) to organize Europe’s investment landscape into an integrated whole. The intention is to foster a European financial system equal to the heft of the EU’s economy — the world’s second-largest — by making it easier for the savings of French workers to fuel the expansion of a Polish tech startup.

The current drive has been underway for a decade, but the project has struggled to take flight. The long list of technical changes needed to integrate 27 individual capital markets is more diffuse and arcane than monetary and trade policy, areas where the EU has made great strides. A prolonged period of low interest rates since 2008 also reduced budgetary pressures, knocking the CMU down the list of policy priorities in Brussels, but now the project is returning to sharp focus.

“Growing financing needs and higher interest rates have led to the realization that we need to increase the pie. The political need for the CMU has been completely reaffirmed,” says Delphine d’Amarzit, Chairman and CEO of Euronext Paris. “We need to work on two fronts: Channel the considerable European savings toward long-term equity investments and create a truly European domestic market for it.”

We need to work on two fronts: Channel the considerable European savings toward long-term equity investments and create a truly European domestic market for it.

Delphine d’Amarzit, Euronext Paris

Green With Envy

An old saying holds that European policy is forged in response to the last crisis, but there is no escaping the toll that the Global Financial Crisis, and the subsequent European Sovereign Debt Crisis, took on the continent's economic growth. European incomes have long lagged average U.S. earnings, but the gap has exploded over the past decade. In 2010, U.S. GDP per capita was 47% larger than in the EU; by 2021, this gap increased to 82%, according to a 2023 study from the European Centre for International Political Economy.

Today, the continent's lagging financial sector represents a burden that may be impeding overall economic growth. For instance, the loss of some of Europe’s highest-profile equity listings to U.S. exchanges in recent years — such as Swedish music streamer Spotify and German footwear maker Birkenstock — has led many to question why European startups are not electing to list themselves on continental exchanges.

In addition, financial bottlenecks are hampering public budgets and inhibiting the green transition. Meanwhile, the war in Ukraine has underscored the value of a resilient continental financial system to fund Europe’s defense spending.

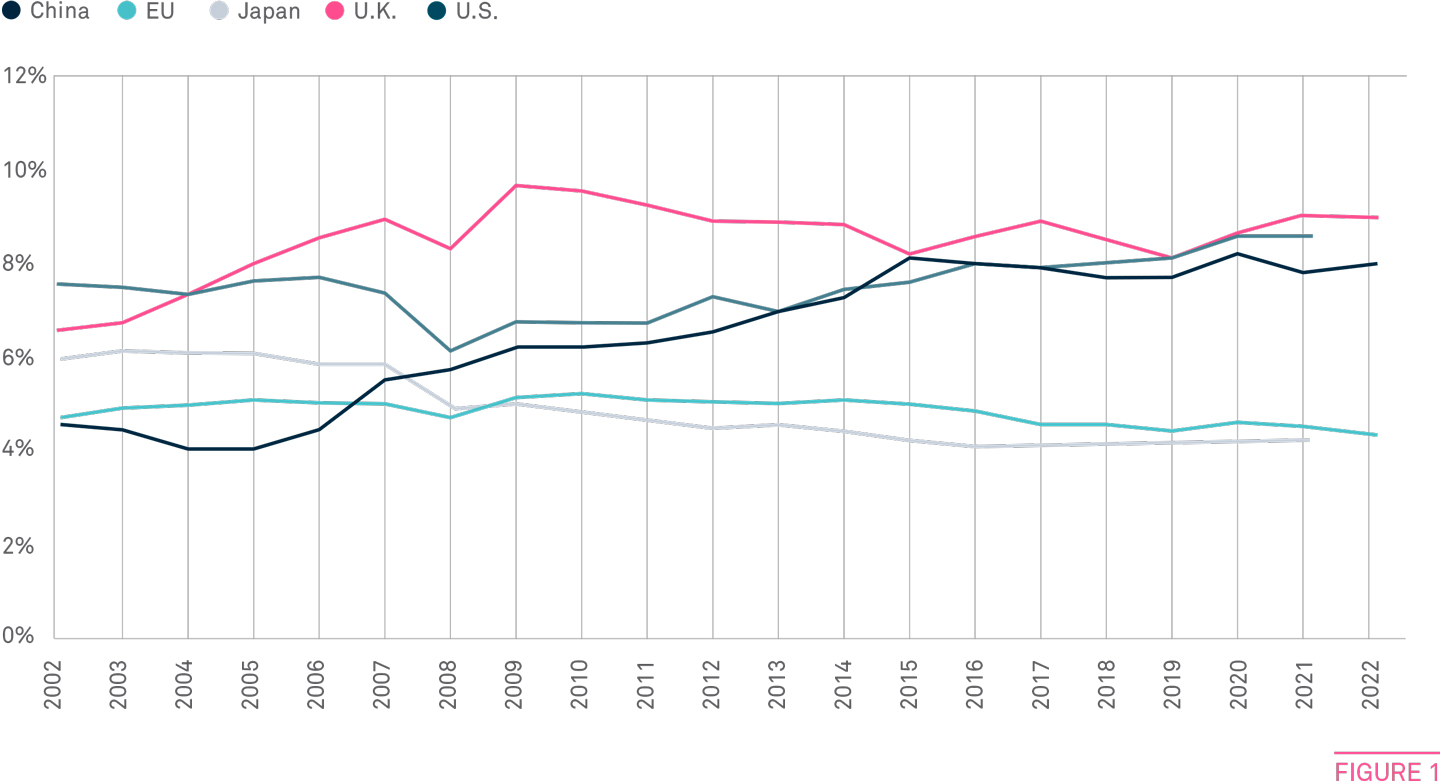

Many in Europe envy the more advanced capital markets in the U.S., where risk-seeking retail investors and multitrillion-dollar asset managers have funded the world’s most vibrant corporate sector. In a measure of the value it contributes to the economy, the U.S. financial industry produces more than $5,000 in per capita income annually, or 9% of economic value added, according to data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. The EU’s financial services sector generates less than $1,000 a year per European, and its economic value — at 4% in 2022 — was the same as it was two decades earlier (see Figure 1).

TWO LOST DECADES

Economic value added by the financial industry in the EU has flatlined in the past 20 years

Source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

“The U.S. is an obvious reference for what the EU wants to create: A well- functioning financial sector that would allocate capital efficiently,” says Nicolas Véron, a scholar at the Bruegel think tank in Brussels, and the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. “But it’s complicated in Europe, because, in Europe, everything is complicated.”

The most recent incarnation of the unified European capital market concept was proposed a decade ago by former EC President Jean-Claude Juncker, but the idea was first articulated in 1966, and though it was raised again in 1999, 2001 and 2009, it has failed to take root.

The U.S. is an obvious reference for what the EU wants to create: A well- functioning financial sector that would allocate capital efficiently. But it’s complicated in Europe, because, in Europe, everything is complicated.

Nicolas Véron, Bruegel

By 2014, growing Euroscepticism in the U.K. seemingly focused Juncker’s attention on the CMU as a potential adhesive that could bind London more tightly to the EU. The intent was to avert any potential diminution of European financial markets that would occur if London were to leave the Union. Accordingly, the CMU presented a vision of a dramatically rejuvenated European capital market with London at its center that could give the U.K. an incentive to remain in the EU.

Brexit happened nonetheless, and the loss of London’s $3 trillion stock market left a capital markets vacuum that Frankfurt, Paris and Milan have struggled to fill. COVID-19 put further pressure on an already languishing EU economy, and more recently, higher interest rates have strained national budgets. Advocates argue that a strong CMU could give the continent a much-needed shot in the arm.

A Fragmented Europe

To understand why investing across European borders can be so frustrating, consider retirement savings. EU member states set their own national tax and pension policies, meaning that there is no continent-wide framework encouraging workers to invest their retirement funds in pan-European instruments. That helps push about €300 billion in European savings abroad each year — mainly to the U.S. — an April 2024 report by former Italian Prime Minister Enrico Letta found.

European capital markets also lack many of the rudiments American investors take for granted. The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) doesn’t have the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC’s) broad discretion to set the rules that govern the operation of capital markets, and its enforcement powers pale in comparison. There is not yet even an official one-stop source for Europe’s corporate financial filings, a tool the SEC has offered via its EDGAR database for 40 years. Europe finally passed a plan to implement a similar system called European Single Access Point (ESAP) in December 2023.

Little happens fast in Brussels, but, at last, CMU advocates are imparting a new sense of urgency. In late May, the EU’s two most powerful national leaders, French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, threw their combined weight behind the project. In an open letter, they called for “a truly integrated European financial market with the banking and capital markets union at its core” as a central agenda item for the next EU parliament, which runs from 2024 to 2029.

A report published on EU competitiveness by Mario Draghi has drawn further attention to the CMU’s stalled progress. Many hope that the next term’s new batch of EC members will be primed to make real progress.

“It’s an important year for change in the EU, and that sets the wheels in motion for a new policy agenda around the CMU,” says Pablo Portugal, senior director for public affairs at Euroclear. “We really need this to be a big structural priority in Europe."

You’re dealing with many different countries’ tax frameworks. When we speak to our clients, they say, ‘For us, Europe is very difficult to invest in.’

Ben Pott, BNY

A More Perfect Union

As policy chatter increases, the CMU project remains less a firmly defined plan than a constellation of related proposals. Still, advocates have coalesced around a few major priorities.

First, they want to make it easier for EU households to invest in long-term assets — both for retirement and general savings — rather than in the low-interest bank deposits that draw more than one-third of European retail funds.

One attempt at a continental retirement account has been the Pan-European Pension Product (PEPP) Unveiled in 2022, the PEPP follows retirement savers as they live and work across different EU member states. The concept did not gain traction, however, because it is designed to complement national retirement plans rather than replace them. Since retirement savings schemes differ markedly from one EU nation to the next, perplexed cross-border savers face a maze of tricky calculations around applicable contribution limits and taxes. The product is generally regarded to have been a failure.

Another new vehicle, a general investment product called the European Long-Term Investment Fund (ELTIF), has not fared much better. These funds failed to generate much interest because of high minimum investment thresholds and overly complicated rules. By 2023, European money managers had only created several dozen funds under the ELTIF construct, necessitating a tweaking of the rules by EU authorities. The ELTIF 2.0 structure was unveiled in January 2024, dramatically lowering the investment minimums, and broadening the universe of private assets in which fund holders can invest, but it is still too early to tell whether the changes are succeeding in broadening investor uptake of the funds.

Letta and other reformers want the CMU to fix this disparity, mainly by persuading member countries to adopt a common set of pan-EU tax breaks for savers, a development that may be game-changing for the broad adoption of a continental savings scheme.

A second CMU goal is to boost lending outside of the financial sector. Securitization, the process of packaging up thousands of mortgages, auto loans and other debt into large securities, is an important mechanism for increasing the availability of financing and credit, but it became a dirty word in Europe after it helped contribute to the 2008 financial crisis.

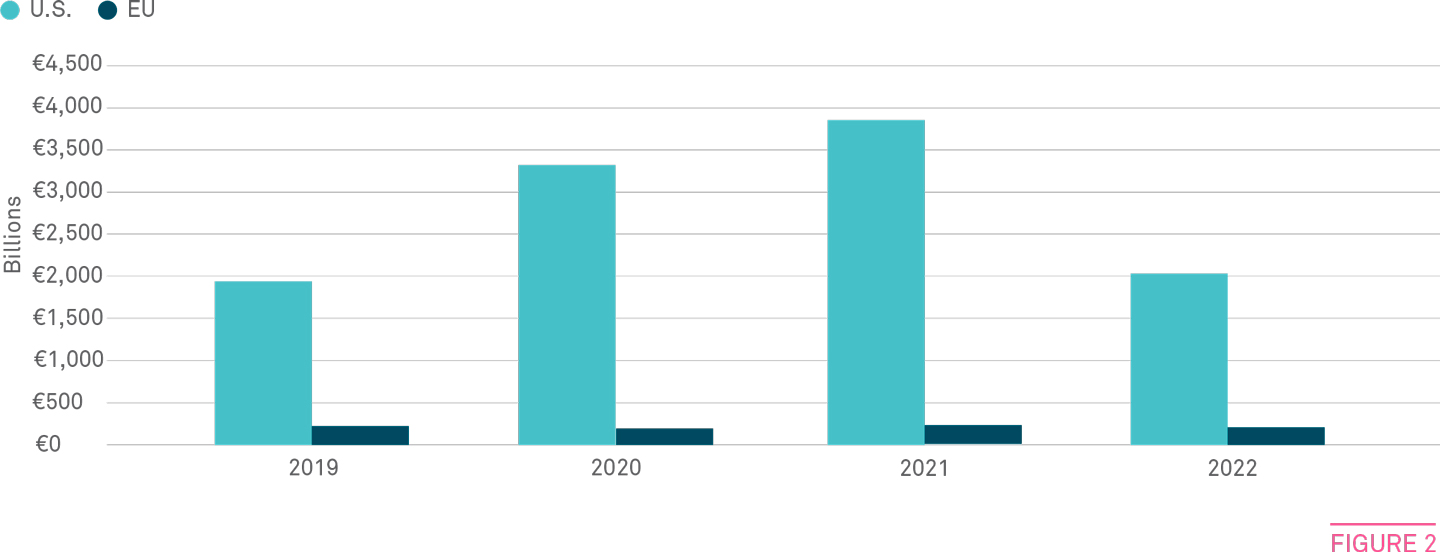

Securitization has returned as a mainstay of the U.S. financial system, in part because it is a cornerstone of how the government-backed home mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac guarantee the nation’s roughly $50 trillion real estate market. In Europe, on the other hand, it has never really recovered (see Figure 2). At just about €213 billion in new issuance in 2023, the market is little more than a fraction of its pre-crisis scale, according to data from the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME). Reformers hope that under the CMU, clearer international securitization standards will be established which might help the industry regain its footing.

EU SECURITIZATION

Issuance is less than one-tenth that of the U.S.

Source: Association for Financial Markets in Europe

A revised securitization framework came into force in the EU in 2019 that introduced common rules on due diligence, risk retention and transparency. The rules were further tweaked in 2021, and, as of the EU’s last update in 2023, work was ongoing to create a pan-European framework for “green securitization.”

In a report earlier this year examining CMU proposals, former Bank of France governor Christian Noyer called for a much more ambitious securitization initiative: The creation of a European entity akin to Fannie and Freddie for guaranteeing and securitizing mortgage loans. In the U.S., he noted, Fannie and Freddie issuance makes up 75% of the securitization market.

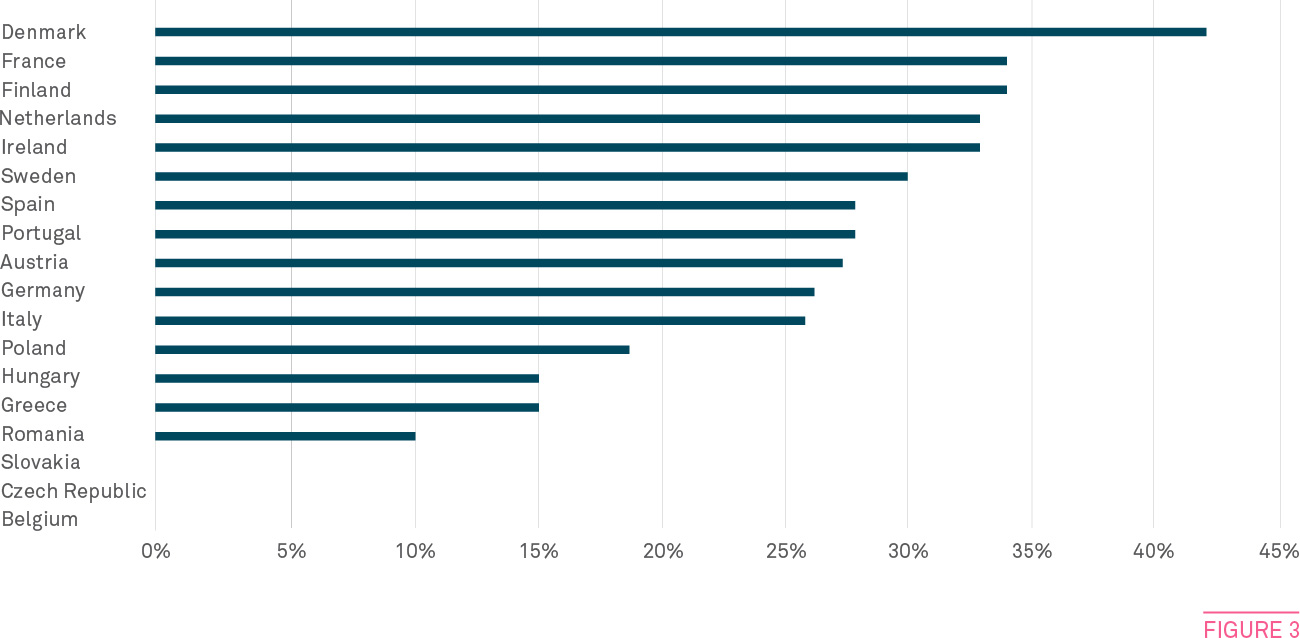

Tax wonks also hope that reformers can work out a better way to divide the fruits of cross-border investments on the continent. Today, an investor in Stockholm earning income on shares listed in Milan will likely receive a Swedish tax bill, even though the Italian government has already withheld taxes on these earnings. Under a network of European double-taxation agreements, the withheld funds can theoretically be reclaimed from the Italian government, but traders grumble that these transfers move at a glacial pace. Complicating matters further, capital gains taxes oscillate wildly across the continent, from completely untaxed in some nations, to being taxed at rates broadly comparable to earned income in others (see Figure 3).

A TALE OF TAX POLICIES

Capital gains taxes range from nonexistent in Belgium to over 40% in Denmark

Source: Tax Foundation: Capital Gains Tax Rates in Europe, 2024

While many elements of the CMU have been percolating for years, these new economic realities are at last focusing attention in Brussels on developing concrete ways to make investing in Europe easier.

“You’re dealing with many different countries’ tax frameworks: Some are very advanced, supporting electronic submission and reclaims, whilst others are very slow and manual,” concludes Ben Pott, international head of public policy and government affairs at BNY. “When we speak to our clients, they say, ‘For us, Europe is very difficult to invest in.’”

Matt Grossman is a freelance writer based in New York.